LANDSCAPES

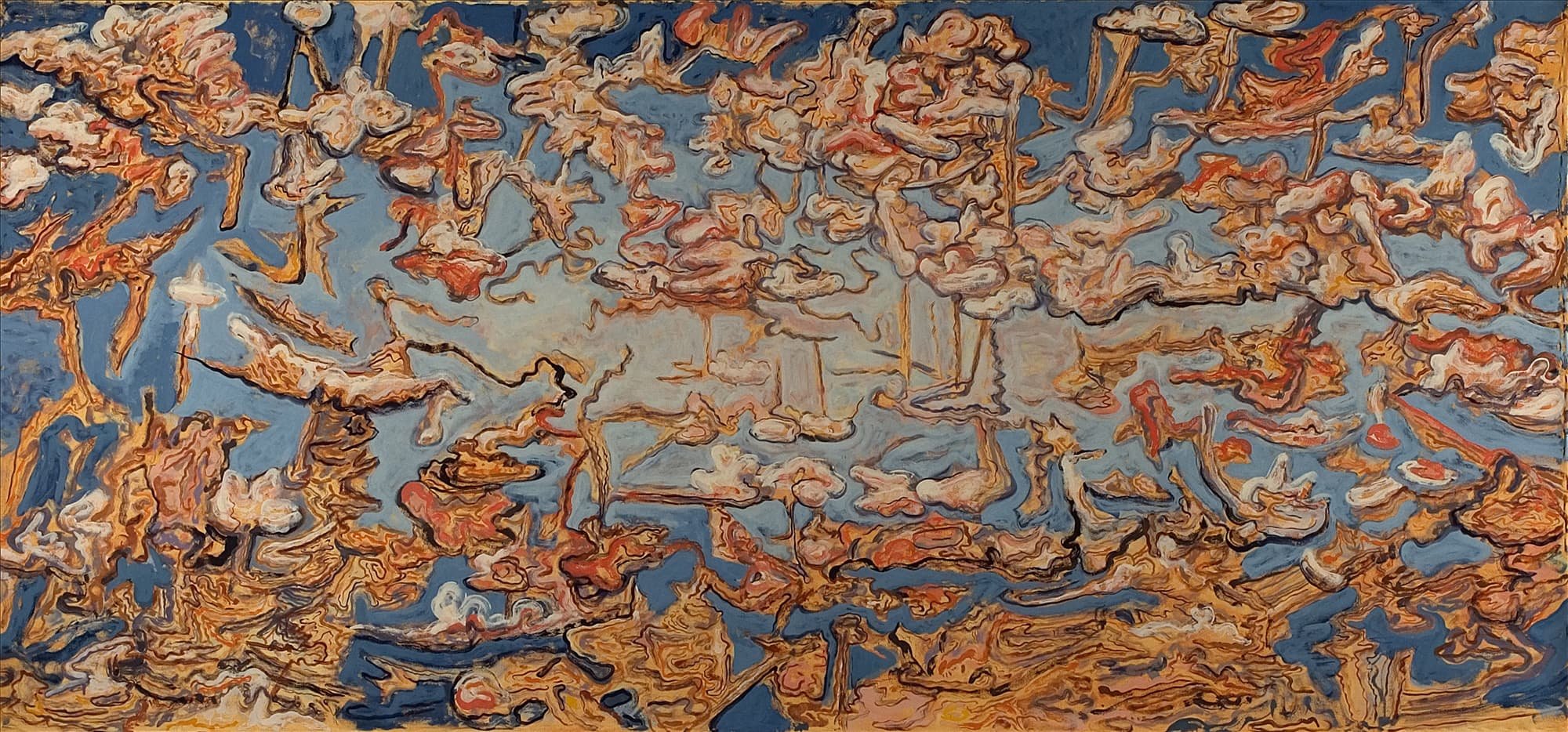

Planetarium

Oil on Canvas / 68 x 110 inches

2005

ARTIST STATEMENT

LANDSCAPES : Toby Cole

My most recent work grew out of a series of paintings based on memory, my travels, and experiences. Initially I was drawn to a scrubby piece of land on a mesa overlooking a nameless canyon in a remote corner of Colorado. On the surface there is nothing extraordinary about this piece of land. It is surrounded by territory controlled by the Bureau of Land Management and is very far from anything. A mountain lion lives out on the point, and down a dirt road are some natural gas wells. Scattered around are the homes of a few dry farmers descended from the homesteaders who showed up years ago. The surface of the mesa curves gently and at its highest point sits an old dried out spring and the remains of an ancient pueblo. A bean field cuts through its midden pit, and every year bits and pieces of the past show up when a farmer, James Shear, plows the field. Human bones and broken pots lay in the dirt exposed to the sun. These things that come up out of the ground all have their own stories.

I have always been fascinated with what might be lying underneath my feet, under stones, or underground and this interest is reflected in the odds and ends scattered about the foreground in the early paintings: broken pieces of sandstone, dead branches bleached by the sun, and clumps of desert weed.

When I worked from memory my ideas were sometimes very grand, but I never made careful plans and rarely sketched. Instead I would impulsively paint, often energetically. The images in my mind were impossible to replicate, yet I found it was the unexpected things that turned up in my paintings that interested me most. I discovered that as the first paint hit the canvas the course of the paintings would be changed forever.

My work made the real transformation to what it is today when I decided that I could simply paint without knowing exactly where I was going, and eventually my marks, movements, interests, and everything could merge. I tend to throw a lot of stuff in my paintings. I wanted to get lost and skip around in the slop.

I gave myself some ground rules. The first was to accept every mark. I was never to erase, blend, fudge, or fuss. I would accept the good with the bad and I was to never second guess what I was painting. The second rule was that, no matter what, I would paint myself out of any of the dead ends that I might find myself wandering into with my wavy line. The third was that I decided to pack in as much information as I could and make these paintings insanely complex. I used a slow, sloppy, linear approach; as I would paint, I would wait and watch to see what might happen.

I don’t exercise any direct control over the evolution of the imagery in my paintings. The things that I am exploring seem to have a nature of their own. I simply paint with the knowledge that something, whatever it might be, will eventually happen. I allow myself to work in the dark, so to speak, painting something I can’t quite see. Often I see myself painting on an invisible surface lying directly underneath the canvas, a sort of alternative world present in my imagination.

The paintings are large in scale and rectangular, but the edges of these works are informed by the organic shapes within the imagery. Having no firm boundaries or edges, the paintings present new issues in distinguishing figure and ground, with multiple variations within the same painting. It is my hope that these new works should serve to make visible a world which has no correlate in our ordinary perceptions. What is important in these paintings is not only what happens in front of your field of vision, but what is going on behind your eyes.

Clumps of soil, lichens, sticks, dead twisted ancient juniper trees, living and dead grasses, mormon tea, yucca, sage, rabbit brush, cottonwoods, cholla, bits of sandstone, dirt, loose red dirt, detritus, sherds, bones, awls, metates, coyote and bear scat, animal tracks, rock strata, topographical maps, arroyos, deep red hematite stained sandstone, and cumulus clouds, all had became a natural part of my visual and imaginative vocabulary. I allowed myself to free associate. With paint I began to travel through these little landscapes, wandering through goosenecks, wriggling around the micro environments of cryptobiotic bits of sod, and to bubble around the edges of billowing, ballooning cumulus clouds. Blocks of sandstone tumble off of mesa tops. Twisted ancient dead juniper branches sprout out of clouds and curl around transforming themselves into anthropomorphic figures like whipping kachinas. Rocks mutate themselves into clouds. Clouds become bodies of cryptogamic soil. Arroyos become snakes, waterways, and branches. Mutating bodies of dirt, cumulus, and rock spread out on my canvases connected by roads, wind, branches, twisted tree trunk, and wriggle.

There were times, after I had been painting for extended periods, I would go outside and see the same patterns and images in the clouds that were in my paintings. At first I thought I had discovered new patterns in nature, but in fact the paintings had changed the way I perceived the world. I think we see what we want to see. What we see is not necessarily real. The only thing that might be real is how we see. Imagine a red velvet ant walking with it’s twitchy steps through the grass. What it sees could not be less interesting than what we see, and we will never get to experience the world as does the red velvet ant. I want my paintings to ask questions that might never be answered.

Anthema

Oil on Canvas / 64 x 48 inches

2004

Orange Cliffs

Oil on Canvas / 58 /76 inches

2004

Big Wiggly

Oil on Canvas / 64 x 95 inches

2004

Purple Burst

Oil on Canvas / 64 x 74 inches

2004

Space Bodies

Oil on Canvas / 64 x 110 inches

2004

Citadel

Oil on Canvas / 64 x 110 inches

2004